My sister Huda’s chest tightens a little more each day. The smoke from wood fires, the acrid dust of bombed-out buildings, and the polluted air from explosions in southern Gaza have left her struggling to breathe. She is the mother of five children: Eman, age nineteen; Raghad, seventeen; Abdallah, fifteen; Ebrahim, thirteen; and Mohammed, eight.

Huda’s family once lived in Gaza’s southern city of Rafah, in a beautiful three-story house, with a backyard and a small garden in the front, which was completely destroyed shortly after the army entered the city. Now they take shelter in Al-Mawasi, a narrow strip of land further west, at the very edge of the Mediterranean. They have been displaced four times since the war began. When I speak to her—usually by text and sometimes by call if the internet holds—her face is streaked with tears and her voice broken by exhaustion.

Her days begin with water, or more precisely, the absence of it. Each morning, she sends one of her boys on an hour-and-a-half-long journey by foot to stand in line with a plastic gallon jug at a charity post in Khan Younis. Sometimes, after hours of waiting, they come back with a few liters. More often, they come back with nothing. And when they do get water, it is cloudy, salty, and contaminated. “But it’s all we have,” Huda told me. Their attempts to filter the water through pieces of clothing often fail; they are forced to drink it dirty most of the time.

The little they drink doesn’t sustain them. The little they eat doesn’t nourish them. Shops are stripped bare, the shelves emptied long ago. Water, the quiet spine of maternal health, is largely broken. When food appears, it is sold at impossible prices—a kilogram of flour can cost anywhere from forty to a hundred shekels (ten to thirty dollars). Huda watches her children grow thinner and weaker by the day. Illnesses follow one after another: diarrhea, fever, skin infections. There is a makeshift clinic in Al-Mawasi run by a charity, and Nasser Medical Complex still operates nearby, but medicines are scarce and doctors overwhelmed. “I can’t treat them,” Huda said. “I can only pray they recover.”

I know this pain all too well. Before leaving Gaza in April of 2024, I lived through the collapse of a medical system that once held mothers and newborns in its fragile care. I saw hospitals reduced to rubble, women giving birth without anesthesia, and babies entering the world in chaos. It broke my heart walking down the streets where I grew up and not recognizing them. Destruction was all I could see. Every landmark I knew when I was young was gone. I carried my two-and-a-half-year-old son, Rafik, through hunger, fevers, and nights where my arms were the only shelter I could offer.

Even shelter offers little relief. Since the early days of the war, Huda’s family has lived under canvas. The tent buckles under the heat of summer and does nothing against the bone-chill of winter nights. It offers no protection from shrapnel or the insects crawling across the sand floor. Huda sweeps the dirt daily, but the earth always wins. “Even the food I prepare sometimes has sand in it,” she confessed. “I have no kitchen or clean place. We live as if buried in dust.”

***

In Gaza, pregnancy has become a gamble. Fifty thousand expectant mothers try to survive, if not for themselves, then for their children. I imagine them counting contractions against the rhythm of shelling, wondering if labor will begin while the ground shakes beneath them. Instead of hospital bags, they prepare with scraps, like a blanket tucked into a plastic bag or an extra dress folded under a child’s head in the shelter. The older women whisper advice, in place of missing doctors. In the corners of crowded classrooms turned into shelters, mothers-to-be pray they don’t give birth at night, when ambulances cannot come.

Saja Nashwan, twenty-seven years old, who was my friend in college, endured her entire pregnancy under these conditions. When I spoke to her, she described the fear and hunger that wrapped around her body as tightly as the war itself. “As a mother of two, who spent my pregnancy and childbirth during the war, I suffered in many ways,” she told me. “The hardest part was the constant fear: where would I give birth, how, and when? There was no transportation at all. At the start of my pregnancy, I had severe iron deficiency and weakness. It was nearly impossible to get proper prenatal checkups because most hospitals only handled emergencies.”

Her delivery, in July 2024, was a cesarean section without painkillers. “It was extremely difficult. There were no effective anesthetics available.” Childbirth without anesthesia has become another battlefield. Al Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, once the territory’s largest medical complex, was largely destroyed in the spring of 2024, leaving mothers to give birth without reliable pain medication, sterile space, or postnatal care. Each month, thousands of women are expected to deliver in hospitals with scarce fuel, intermittent electricity, and dwindling stocks of oxytocin, antibiotics, and other essential drugs. The women who can’t make it to a hospital must give birth in rubble or on the street.

Saja’s struggles only worsened after the birth to her son, Nabil, who is now one year and two months old. “From the beginning, there was a shortage of milk and diapers, and when we found them, prices were outrageous,” she recalled. “There was no clean water, so we had to buy bottled water for the children at exorbitant costs, and even that was very hard to find.” When her baby turned six months old, she tried to introduce food but found little that was safe to give. Providing healthy, clean food to her newborn and to her daughter, Arjwan, who is almost three now, felt almost impossible. “But we kept trying anyway.”

Like many people and their families, Saja, who is originally from Gaza City, had fled bombardments within the northern parts of the Strip with nothing but the clothes on her back. In the markets, it was virtually impossible for her to find children’s clothes or shoes. At the time this article was written, Saja and her family were still trapped in Gaza City, unable to flee south despite the intensified bombings around them and the army positioned close by.

Now newborns and children in Gaza face even harsher conditions than when Saja gave birth. Hunger defines pregnancy, early childhood, and the fabric of life itself; today, more than half a million Gazans face starvation. For breastfeeding mothers, this is not abstract: inadequate calories reduce milk supply, forcing infants to rely on formula and clean water that are often unavailable. For mothers who are pregnant, the risk of premature delivery is high. And that is to speak of the lucky ones.

***

I sometimes think about what this war means in the delivery room: an exhausted mother arrives after walking for hours because there is no transport; or a midwife washes her hands with bottled water rationed cap by cap; an operating theater where the generator coughs and dies mid-cesarean. In the first few weeks of the war, UN agencies cautioned that mothers and newborns would be forced to pay with their lives.

Nearly two years in, the warnings have become a grim ledger of preventable harm. Over 40 percent of pregnant and breastfeeding women in Gaza are battling malnutrition. At the time of writing, the death toll from hunger has risen to 428, including 146 children. They have joined at least 66,000 others who have been killed in Palestine since the outbreak of the war.

Motherhood has always been the center of my life. In Gaza, before I fled, being a mother was about providing simple joys for Rafik—fresh bread, a walk to the sea, a new toy when I could afford it. After I was forced into exile, motherhood took on a different meaning: A struggle to carve new memories for my child and erase the trauma still lingering in his head. I am now far away from Gaza, but I remain in daily touch with mothers still inside, listening to their stories through broken internet connections and hurried dispatches. Their voices remind me of the life I left behind, the one they continue to endure.

Listening to Huda and Saja, I cannot separate their stories from my own. For the first seven months of the war, I was in Gaza, too. Rafik’s hunger was the hardest to bear. At night, when he woke and asked for food, I often had nothing to give him. I held him, helpless, while his small body trembled. The guilt never stopped—for not finding water, for every spoon of borrowed formula, or for watching babies shrink against their mothers’ breasts. Terrified of bombardments and unable to provide him with the warmth and care he direly needed, I couldn’t sleep most nights.

As mothers, we’re supposed to promise joy to our kids. I couldn’t even promise him a crust of bread. In exile, I hold these stories with me. Rafik and I are safe now, but safety feels heavy. When I open my fridge, guilt floods me. There is food inside and clean water at the tap. I pour a glass and see Huda’s son standing in line with an empty vessel. I cook dinner and hear Saja whispering that even milk was impossible to find.

Rafik plays now in the park near our apartment, and his laughter carries into the air, free from the roar of jets. I watch him run, but I also see him as he was—crying for bread in the dark and pressing his face into my chest. I can’t separate the two. Although he was only two and a half at the time, he still seems to be affected by what he went through. His nightmare is to sleep. He is terrified by the dark. He feels the need to escape every time he hears a sudden, loud sound, and he has never loved the sound of planes or fireworks since.

I still can’t sleep most nights. After putting Rafik to bed, I sit with my phone, waiting for messages to load from Gaza. Sometimes I scroll for hours, searching for news, for proof that Huda’s children are still alive and that Saja’s baby has survived another night. I am holding my child here, while part of me is mothering there, and grieving always.

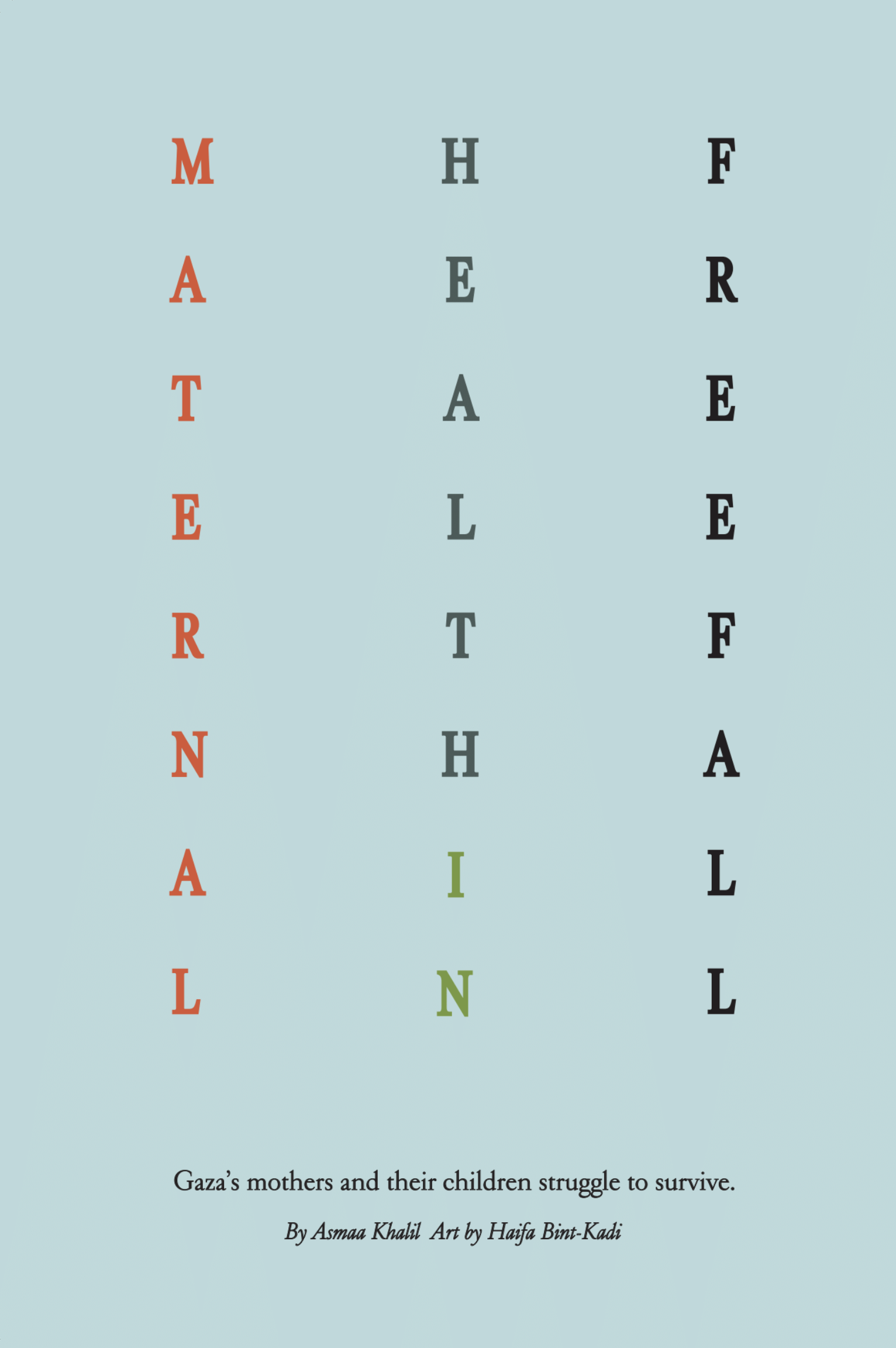

By Asmaa Khalil, a Palestinian writer and teacher of English from Gaza, now living in exile.