She had made it clear on the very first day that they did it better in her country. Everything? Well, yoga at least. We didn’t know anything else about her. And to be quite honest, we didn’t learn that much else later either. We had other concerns. We weren’t at teacher’s training to make friends, something no one dared say out loud but everyone thought. Most of us were already friends anyway, or something close to that.

She was pretty but pretty in the way you knew was not from here. It was clear her nose had undergone a surgery that was routine for girls like her, her eyebrows were a bit too perfectly waxed, and she of course wore too much makeup. Her hair was incredibly long, and she wore it in perfect loose waves (which no one did) to yoga teacher’s training. Jewelry, makeup, hair that was done, and non-yoga clothes—once she wore a leather bodice. It was all part of the deal with her, we soon realized.

I suppose she also looked at us like we didn’t make much sense. Us: plain, pale, tattooed, mostly blonde hair, wrinkles and freckles. Our uniform: sports bras and yoga pants. Our smell: sweat and lotion, no perfume, no oils. Natural, but not without ambition. We had carved our bodies into something gangly, lanky, and slight, while she arrived loudly voluptuous, robust, abundant. We tried not to stare; we didn’t have a context for all that in a space like this. Of course we weren’t there to compare, but in yoga we observe. Not judge, but observe. We observed that she was, at the very least, nothing like us.

I don’t know what we expected when they said a new girl straight from wherever she was from would be joining us. I suppose we expected her just as she was, but her opposite was also possible. We saw different versions, two specifically, of the same girl. The modest one, and the less modest one. We didn’t, of course, but we wanted to ask her about bellydancing; we didn’t, of course, but we wanted to ask her about the long black veils. We wondered if she knew we were people who used to watch the news; we wondered if she thought our education was lacking. But of course, we didn’t say a thing. We didn’t want trouble and we had to assume neither did she.

But as much as she didn’t fit in in Santa Monica, she did know her yoga. She wasn’t better than us, necessarily, but you might say that she was, well, maybe more adept at embodying it. You could just tell from her movements. You could see she grew up with it. You could see that to her, it had mattered more.

In a way, we actually did try to be her friend, for a while. But she did not make it easy. We thought maybe it was the language barrier, the cultural differences, who knows.

One time this girl from the East Coast asked her about yoga being from her country and we all wanted to die.

“I am not from India,” she corrected.

“Oh I’m sorry—I thought, you know, South Asia!” the girl blurted frantically.

“West Asia, not South Asia,” she said quietly. Like it was intended just for herself, or the people she could later tell about this—maybe to share a hard laugh, a disgusted eyeroll, a kind of long weary sigh.

But at that moment she didn’t want to shame the other girl, which impressed us all so much. It showed a certain grace that was way beyond us.

One time I saw her eating rice while sitting on a toilet in an open bathroom stall. We were told not to eat two hours before class or two hours after, and since the sessions were four to five hours long—we wanted to get certified, and that was what it took—we got hungry. Most of us shoved small morsels of granola bar in our mouths in little lulls here and there, as we had to keep eating a secret from our instructor, of course. But she had the audacity to pretend to go to the bathroom, and once, when one of us actually needed the bathroom, we saw her shoveling basmati with the stall door open, sitting there on the toilet like it was a chair at a restaurant. We had a good laugh about that, but also we were jealous we hadn’t thought of it.

One time she and the teacher had an argument. It was about crow pose. She believed her crow form was perfect but our teacher thought differently. The placement of her knees was off, the teacher argued, but she said in her country, they taught it this way. “The way I do, the crow can really fly freely,” she explained.

We found that comment exhausting. Especially the way she said freely.

“I am not trying to challenge your sense of freedom,” our teacher said. We were proud of our teacher. She knew what she was doing and she was not going to back down.

They kept going back and forth, the rest of us just hovering, frozen crows, unsure how to proceed.

Our teacher grew increasingly flustered. No one had challenged her before. She ended class early.

“It takes a lifetime to master form,” our teacher said.

“Yoga is not about mastery, we are all students of the art,” our teacher said just as often.

“Yoga is,” our teacher would say and then pause in this specific way before spoon-feeding that final word to us like we were baby birds, “mist.”

By the time we got to the end of the three-month training, everyone accepted her, more or less. She was going to go back to her country after this and so who knew what this all meant for her? Still she seemed to be studying hard for the final—we all had to pass a written test, plus give a class demonstration of a fundamental pose. We imagined she’d be worried since English was not her first language, but she expressed no concern. She always came early and left late—you’d see her deeply immersed in the yoga books before and after class, on the mat and in the parking lot. An older man in a luxury car we couldn’t make out was always picking her up. We didn’t know if it was a father, an older brother, or a lover—and we didn’t dare ask.

On the day of the final, some kind of bloodshed in her country was all over the morning news. We didn’t read the news—it’s LA, who needs news, we used to joke—but we heard her talking about it outside the door in a mix of English and her native tongue, practically yelling into the phone. Her voice was breaking in a way we had never heard. Usually, even with her accent, she sounded so sure of herself—but on the phone that day she sounded like a young girl. She sounded scared.

We didn’t know what to say, so we said nothing.

We had our own worries—the yoga final was on that very day. Months of hard work, thousands of dollars, dreams of being a yoga teacher, all on the line. We could not fail.

The written part came and went and most of us agreed it was pretty easy—easier than we imagined it would be. But forty percent of our grade was the class demonstration. We could get a perfect on the written exam, and if we failed the demo, we’d fail the whole thing. It was horrifying to think about. The academy could not recommend us for certification. A nightmare. We could always enroll in another teacher’s training at a twenty percent discount, but still. We would never get over it.

Many failed.

We had heard of many who had been there before us and finally just failed. Our teacher rarely spoke of this, but in our circles, we had heard. We let those tragedies rattle us. And we told ourselves not us. We could only afford to win.

And so, one by one, we did our demonstrations. Every single student was assigned a pose and we were to teach it perfectly. We didn’t know who had what, so it would be a surprise for us too. Some of us had memorized scripts—some boasted that they did not need to, that the goddess herself would be in them and it would have to go well. Regardless everyone looked prepared that day. Smiles, tense smiles, but smiles. There was an almost-professionalism in the air that we didn’t always notice.

The teacher purposefully stressed us out by having us go in reverse order, as in, the asana but backwards. We began with savasana, “corpse pose.” Assigned to an actress/waitress. We all envied her as it was pretty easy—but deceptively easy our teacher reminded us. It was, in her opinion, the hardest pose to perfect, even though for outsiders it was just a person lying on a mat, eyes closed. But the key was absolute repose.

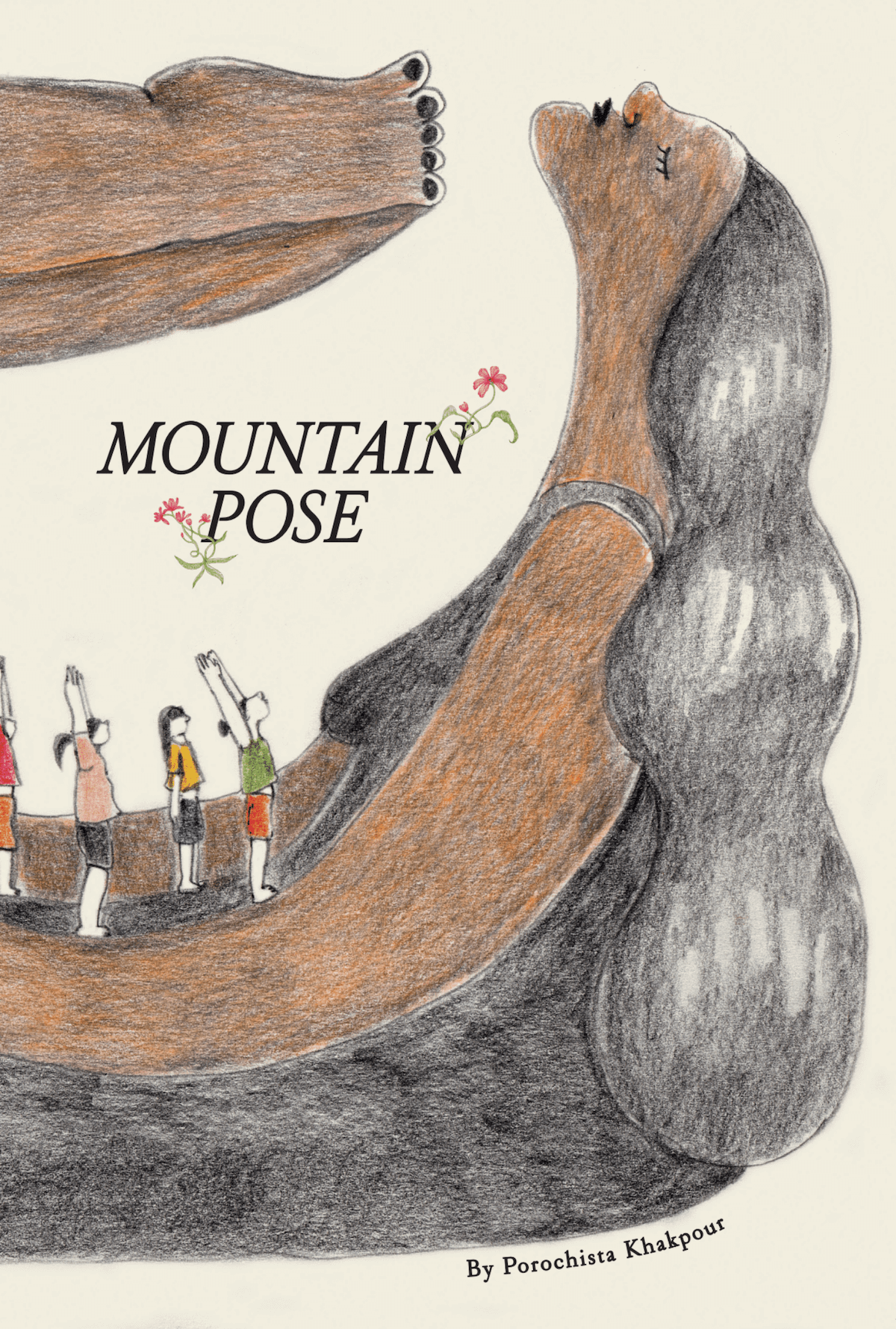

The teacher assigned her tadasana. Mountain pose. Which meant she was going last.

In a way, much like savasana, it looked like doing nothing: just a person standing on their mat. But the teacher had also mentioned this would take a lifetime to perfect: it was all about ideal alignment. That’s how you relaxed into a straight line.

In any case, by the time the teacher got to her, we were all exhausted and ready for it to be over. We planned to go home in high hopes, and wait for our email telling us if we passed. That was it: pass or fail. But she took her time going up to the platform, in no rush at all. And why should she be? We each got five minutes for our poses—it was timed, and only one person went over. (A few seconds; she was forgiven.)

And then there it was—she went from a casual stroll, almost slumping stepping to the center of the platform, to the grandeur of the asana. To perfect stillness anchored in ideal posture. Stillness pulsing with strength and flexibility all at once. One second and we could already tell that she had passed.

But she took it very seriously, and it was clear she did not assume that she would pass. She very carefully, in her very studied English, walked us through the basic mechanics of standing straight and still at the start of our practice.

She asked that we stand with our feet parallel, big toes touching, heels slightly apart. (You could also keep your feet hip distance apart, if that was more comfortable.) She asked us to lift and spread our toes and then let them settle back on the mat. She asked us to feel our bodies balanced absolutely on the soles of our feet, our foundation strong and stable. She asked that we lift our sternums straight to the ceiling, and broaden our breaths, expansively, through the sides of our chests. Our shoulder blades, she said, were to draw toward each other and down our backs, away from our necks. Our arms were to be completely relaxed at our sides, palms forward, fingers in a total release. Our pelvises were to be not tucked or thrusted, but elongated down our backs through the top of our heads. Our heads were to be balanced directly above our bodies, chins not forward or down or back, rather, floating atop our necks. Our jaws were to be unclenched and in abandon, our entire face effortlessly in place. Our gaze was to be straight ahead, eyes not wide open or closed shut, but simply, relaxed—a relaxed and fixed gaze.

“You are exactly where you are meant to be, right here right now,” she said as she wove between us standing in our postures on the floor. “You stand like a mountain, unconquerable, strong, solemn. You belong here. Nothing can uproot you, nothing can destabilize you, nothing can take you away from your place right here.”

We heard her voice break a bit, like she had on the phone, and later someone said that the entire lesson, there were tears streaming down her eyes—but the studio lights were dim, and we didn’t all see.

“You are where you belong. Your feet are grounded, your body is in its correct place, there is no questioning your existence in this room. Slowly let your exhales grow longer than your inhales, let your body go from strength to surrender, all while still. Still.”

We held the pose as she instructed, which was probably the longest any of us had ever thought about mountain pose. She stopped pacing and took her spot up front again, leading us in the pose.

“Find peace in tadasana. Find your essence in this stillness. So much is happening for you to be this still. This peace, this balance, this promise in your very being, hard won.”

Her voice broke again. She had her back to us, in her mountain pose, and somehow it seemed more perfect than any mountain pose ever. We tried to squirm our bodies into that degree of majesty but couldn’t.

“One day,” she went on, “this will be your final stillness. Tadasana is savasana. May you rest where you wish, where you belong, may you find that even far from home your body is home, your mind is your shelter. May all beings be free, they tell us, but may we really remember this in our every breath. And may we recall the price so many others pay for our freedom.”

She had us but then she was losing us. We didn’t want to her to fail, but we were here for one thing and this was now something else. We didn’t ask for metaphors. Yoga is mist—sure. But this? We knew enough about her country to know what it did not have. We didn’t know to what extent she was upset at our country, or if it was even her country now. She never became our friend, so how could we even ask?

“One day, one day.”

Her voice was all shards, like a piece of glazed pottery giving into some force beyond it. We looked toward the teacher, who had her eyes glued on her, a student, in a way we had not seen before, our teacher’s hand at her own throat, as if she too had something she had to keep together, lest it fall apart.

But I think it’s safe to say we didn’t buy it. Not really. We had to assume that.

After class, We all said our goodbyes, exchanged social media accounts and phone numbers, and made all kinds of promises. But not her. We heard her sobbing in her native tongue to someone on the phone. She left quickly, almost early, without a nod or a wave.

We told the story over and over, and the story did what stories do. In one version she wasn’t crying but screaming. In another version she threatened us, told us she hated our people and what we had done to hers. There was a story where the police got involved. Another where she ended up in a psych ward. In one, she eventually started teaching at the studio. And in a version after that, her family bought the studio.

But the truth was, we never heard from her again. I heard from another student that when the teacher emailed her her congratulations, the email simply bounced back, return to sender. The same address she’d been using all those months with its impossible spelling, and the second the final was over, so was she.